Story of Ido Masao

My beginnings: the great spaces of China and the vast nature of Iwate

Masao Ido(right), age 1, with his brother

Right after the end of World War II, in November 1945, I was born in an air-raid shelter in Beipiao, a town located in northeast China. The following year my parents managed to return to their home town, Kyoto, with my older brother and me, still an infant. We four had survived many life-or-death situations in the chaotic circumstances of post-war China. Soon after returning to Kyoto, my father got a job in Iwate Prefecture, northeastern Japan, and the whole family moved there.

Although Japan’s land and people suffered greatly during World War II, with everyone beset by great poverty, it was also the beginning of a period of hope when the whole nation put energy into reconstruction. The history of post-war Japan overlaps with that of mine, since I was born in the year the war ended.

During my elementary school years, I was a very active boy. As soon as I came home from school, I would toss my school bag through the door, climb the hill behind our house, and play until sunset with neighborhood boys. I have few memories of studying; yet, I loved painting and won many prizes in school contests. I remember being awarded in front of the whole student body. But what made me happier than anything was to receive a 24-color Cray-Pas set, sought after at the time, or other such art supplies. Those childhood days spent surrounded by warm and straightforward people, and the harsh but wonderful nature of northeast Japan, formed the basis of my future life.

However, when I was fourteen, in the winter of my third year in junior high school, just before graduating, I was forced to move back to Kyoto because of my parents’ separation. It was a painful experience. I felt as if I were being deprived of my whole existence. Being just a child, I couldn’t do anything about that, but I vividly remember making a pledge to come back to Iwate someday in the future.

Kyoto’s fascinating world of beauty and craftsmanship

At the farewell party towards the end of the third year of junior high school

For a person like myself raised in the vast nature of Iwate, Kyoto was a big city with dazzling beauty and a time-honored culture. Feeling lost at being thrown into such an urban ambience from an utterly different environment, I told myself to live with the pride of a Northeasterner. However, in real life, I had to make a choice of whether to go to high school or get a job. Since I was a freeloader in my mother’s parents’ household, I wanted to become independent as soon as possible. I decided to work for an electric company and study at night school.

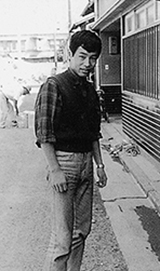

Soon I came to know that Kyoto is a town of handicrafts with many people engaged in its traditional industries. Because I had loved drawing since childhood, this fact excited me. Through my grandfather’s connections, I was introduced to a textile artist and became his live-in apprentice. Reviewing my life now, I believe the decision I made at that time opened up the path that I have followed ever since.

Because I was the youngest there, my job as an apprentice started with sweeping the house, running errands, and taking the dog for a walk. However, my strong desire to go back to Iwate was a driving force that made me work harder to master the textile skills. I practiced brush strokes, copied original works, and made many sketches right after my work was finished every evening, trying to become self-supporting as soon as possible.

Encounter with woodblock prints

Working as a live-in apprentice for a textile artist in Kyoto

I did become independent at the age of twenty. While continuing to dye fabric for kimono and obi sashes for a living, in my spare time I began to create my own artworks and submit them to various exhibitions. A little later, a printmaking friend introduced me to an art dealer, and I was offered an opportunity to hold my first solo exhibition at his gallery. I made drawings with dye-inks and wax on hand-made paper, and called them “batik.” I was twenty-five then, and it marked an important first step as an artist. I can’t forget the thrill of selling my first work.

Soon, when I was beginning to feel a strong urge to create something other than dyeing works, the art dealer showed me woodblock prints by Kiyoshi Saito. The moment I saw them, I got my answer. I was so deeply inspired by his works that I immediately started to study the world of woodblock printmaking.

At his first solo exhibition(Ido sitting on a chair), age 25

I visited carvers’ and printers’ workshops whenever I found time to see a variety of wonderful techniques and understand the long history of printmaking. I was completely drawn into this world.

Carrying on the tradition

Kimono show at Cuisine Shiseido, Tokyo

At the solo exhibition commemorating his first book Poems of Woodblock, age 43

The woodblock print was introduced from China to Japan, where it underwent dramatic development. Japan is rich in printmaking materials: abundant in excellent trees for carving blocks, such as cherry and katsura (cercidiphyllum japonicum); ideal materials for papermaking such as kozo (paper mulberry tree) and mitsumata (edgeworthia chrysantha); and clean water. The sensitivity of Japanese people and their superb craftsmanship contributed greatly to the birth of ukiyo-e, which flourished as a unique art form during the Edo period (1603-1868). I thought these wonderful techniques of ukiyo-e should be preserved and handed down for the future. The first step I thought I should take was to create as many prints as possible by myself using these techniques, so that more and more people would know about this excellent artform.

Then, I considered becoming an eshi (painter or designer) in the manner of Edo-period ukiyo-e production, and engage exclusively in drawing the original pictures for prints. Some people say that print artists should also carve and print by themselves, otherwise they don’t deserve to be called artists. In my opinion, however, artists are the ones who create something new from scratch, while artisans’ job is to realize the artists’ ideas in actual works by employing their advanced skills.

However, year by year artisans seemed to be decreasing in number due to age, without many successors. I decided to create a hanmoto (literally a publisher, but in ukiyo-e tradition it refers to the people or company responsible for the whole printmaking project and sales). I asked carvers and printers to teach young people their techniques systematically. At the same time, I thought of owning a gallery which would exclusively show woodblock prints. In order to realize such a dream, I continued to produce kimono and obi during the day in my dyeing studio as my source of income, employing about ten workers, and made sketches for prints at night. Finally in 1982, I opened a gallery which would serve as a center for printmaking and its promotion.

Another concern I had in those days was the future of the textile industry in Kyoto. Even though kimono were an important source of business here, demand for them was in decline. As a person engaged in the kimono business, I was quite anxious about this situation. In order to encourage structural reform in the industry and rediscover the beauty of traditional designs, I made kimono and obi with my own designs and held fashion shows both inside and outside Japan. Since I started my creative career with textile dyeing, learning so much from this rich world of culture and tradition while pursuing my dreams, I am always willing to do anything I can to help enhance this important Kyoto industry even though I am now away from the kimono business.

My life and the universe: insights from Iwate

Opened a studio in an old farmhouse in Hanamaki

After nearly two decades of creating artworks in Kyoto, I noticed that I had been unconsciously expressing something fundamental in them, something that I could not explain in words. I wondered why I was leading my life in such a way and realized I had felt compelled to do so by some mighty force all those years. Slowly, I became strongly aware of the will of the universe: all living creatures must have been given a life mission by the will of the universe, and it was the same force which drove me to create. That’s the reason why I had this life. Such thoughts became my firm conviction.

In 1994, I was asked to work on a major event held in 1997 commemorating Kenji Miyazawa’s one-hundredth anniversary. He was a very famous and well-loved poet and author of children’s literature. This gave me an opportunity to open a studio in Hanamaki, Iwate prefecture, where Kenji was born. It was inevitable I encounter Kenji’s perspective on the universe. His insight into humans’ inner world and his religious views helped to deepen my artistic expressions. Utterly different from my Kyoto life, I lived alone in a two-hundred-year-old farmhouse, which healed my body and soul completely. Following a desire that was welling up from within, I made a series of works on the theme of the cosmos. Also, in order to put Kenji’s ideas into practice in my own small way, I opened my studio for public use, naming it Hanamaki Bunka-mura (Hanamaki Cultural Village), and making it a center for local art and handicrafts in order to revitalize the area. It was then made into an incorporated nonprofit organization (NPO) and is presently run by volunteers.

With the late Seiroku Miyazawa, younger brother of Kenji Miyazawa

A supporters' group from the Chugoku region visiting Ido's studio and workshop

My mission and roles

The pine tree that withstood the tsunami at Rikuzen Takata

During the filming of the NHK TV program 'Shumi-yuyu'(Leisurely Hobby) shot in the former residential district of foreigners in Kobe

Teaching printmaking for the students' graduation project at Miyanome Junior High School, Hanamaki

In my studio in Kyoto, I completed a major print project Heisei Ukiyo-e: Hundred Scenes of Kyoto in 2008 after spending five years on it. It was an important project for assuring the preservation of printmaking techniques into the future. The idea behind this project was that, even after my passing, printers will be able to reprint these hundred scenes using the blocks (there are about a thousand), and even when these blocks are worn out, carvers can recarve the images on new blocks and continue to print them, since ukiyo-e has no edition numbers. In this way, I can continue to provide jobs for future carvers and printers while the techniques are being handed down. Thus, I can entrust my dream to future generations.

In March, 2011, while I was working in Kyoto, northeastern Japan was struck by the greatest earthquake we have ever experienced. Hanamaki was damaged by the earthquake, but the coastal areas were also hit by the tsunami. Towns and villages were swept away along with the lives of so many people. I visited these areas and saw unbelievable scenes unfolding before my eyes. The houses were all gone, merely leaving their foundations behind, but as I got closer to the seashores, even these traces were obliterated. Suddenly, in the middle of the bleak plain, I saw one pine tree standing. Among a stand of what had been seventy thousand pine trees, only one withstood the disaster. Despite my feeling of helplessness, seeing this miraculous tree I felt that what I should do under the circumstances was to create new works. I began a print series of works in the shape of lotus flower petals called sange, which are traditionally used for Buddhist rituals, conveying my wish for quick recovery from the disaster. Coincidentally, soon after the earthquake, I lost my elder brother, and then mother. Facing the mortality of human life, my determination to complete my mission became stronger.

Living as a painter

Working on a six-panel folding screen

Now I am enjoying painting with a refreshed mind. I am expressing myself freely on folding screens, fusuma (paper partitions), fans, and other surfaces in different shapes and sizes without any restraint. Every day I am discovering new joy in the endless flow of images that well up.

Born in China, making it to Japan alive amid the post-war confusion, spending my early days in the vast nature of Iwate, moving to Kyoto and encountering the traditional arts and crafts, I can’t help thinking that each place I have spent my life in has given me strength and power to fulfill my purpose for living. Looking back at the path I have walked so far, I feel that all my past is linked by a single thread. Being aware of my own mission, I am accomplishing it with the help of so many people. With sincere gratitude, I will continue to walk my path.

Producing a votive painting for Eikando temple

Gallery Gado (opened in 1982)